Article 1: Modern Day Woodblock Printers Still Working In Japan

by Thomas A. Crossland

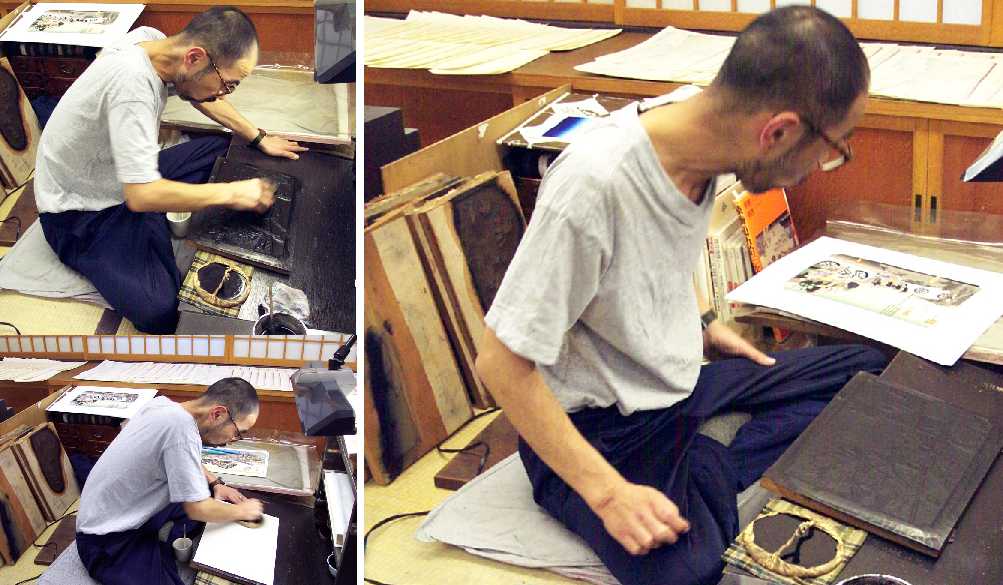

During my recent "family trip" to Japan just this past December 2000, I was fortunate to have been able to both observe and visit with several modern day Japanese artisans during their busy day, at work producing woodblock prints. The series of photographs which follows below will help to illustrate the process. Fortunately, being accompanied by my native-born wife (Hisako), I was additionally able to ask of them several questions about their work. More on that later.

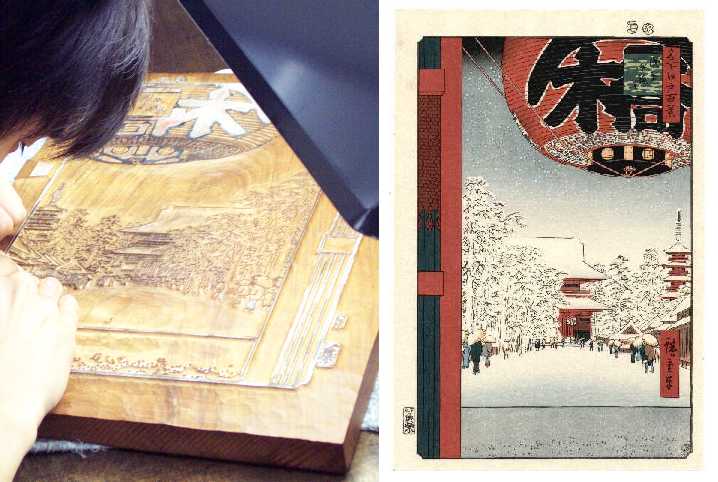

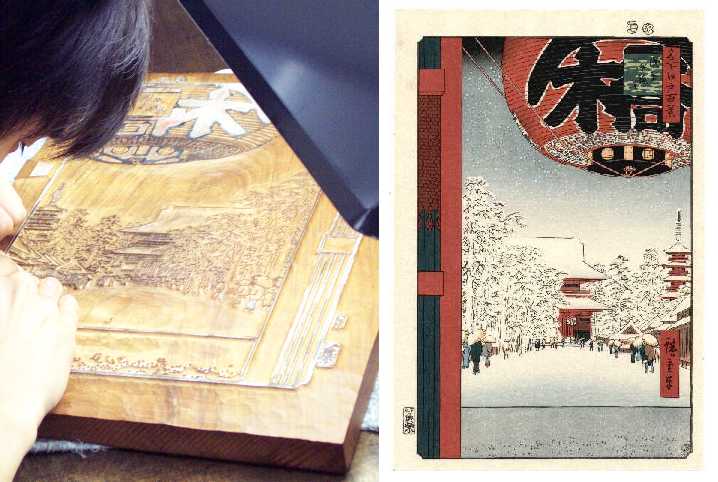

Many of the prints still being produced today are reproductions of well-known and popular images from the mid-1800's. Known as "re-strikes," these woodblocks are printed using sets of newly carved woodblocks which are often so accurately carved and skillfully printed that they rival the quality of the earlier originals from which they were made.

For those unfamiliar with woodblocks, let me briefly explain and describe the multi-tasked effort involved in producing these wonderful works of art. It is a process somewhat similar to that of "inking a handheld rubber stamp which is then pressed against a blank sheet of paper," only in this case it involves a complete set of intricately carved cherry woodblocks, a separate one required for EACH color used.

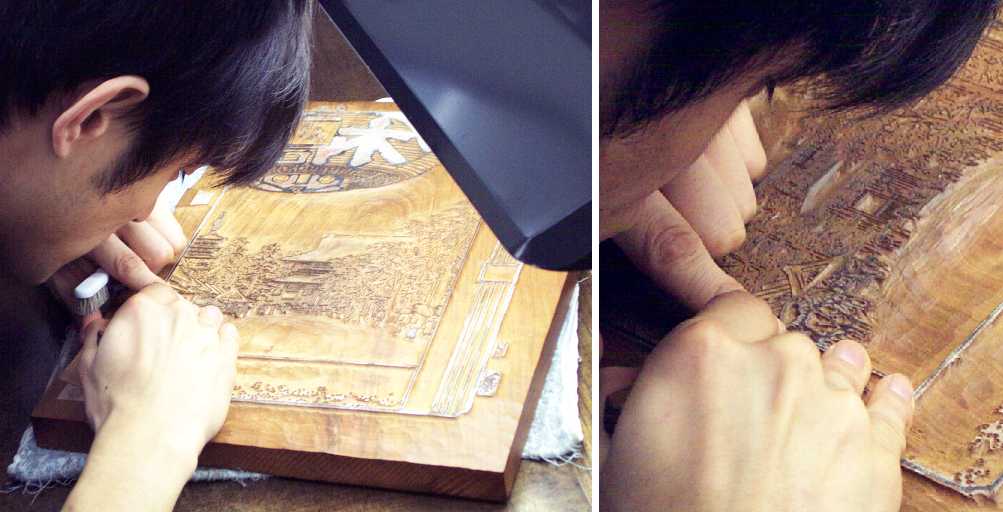

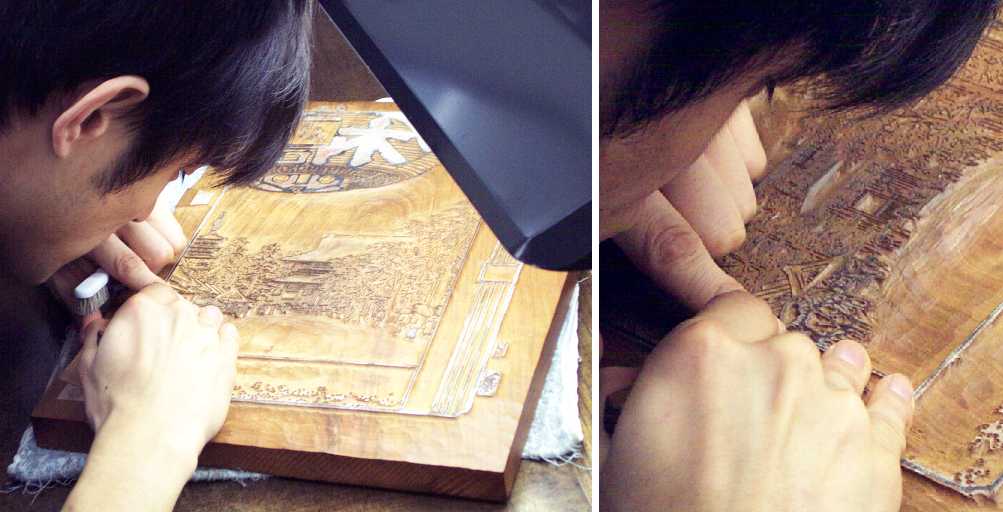

The initial step, of course, involves the use of the artist's original sketch (done on thin paper) which is first glued upside down (must be reversed) onto the flat surface of a cherrywood block. The carver then begins the tedious and very exacting task of carving (through the glued paper) along both edges of all the sketch's lines, resulting in only very thin, raised edges left standing in relief. All excess, "unwanted wood" is thusly carved away. What remains then-after many tedious and seemingly endless hours of work-is known as the "key-block" which is used to print the BLACK outlines seen in the print. Additionally, I should add, also carved into this block's corner is a small raised "corner notch" (known as a "kento cut") along with another short raised "straight edge" along one side. These precise "reference points" are then transferred and carved into each of the additional colored woodblocks, as they are required to ensure perfect alignment (or "registration") as the following colors are subsequently over-printed.

Next, by inking this "keyblock" with black ink, several black-outlined copies are printed (again onto thin papers) which after being dried are similarly glued facedown (always reversed) onto the surfaces of the additional, yet-uncarved, woodblocks. The various areas between these black lines then define the boundaries of each INDIVIDUAL color. Again, the carver then carves away much of the surfaces of these various woodblocks-one woodblock for EACH color required-in each case leaving standing the various areas needed to print that specific color. Finally, after weeks and weeks of precise carving, this multiple set of woodblocks is completed, allowing the printing itself to finally begin.

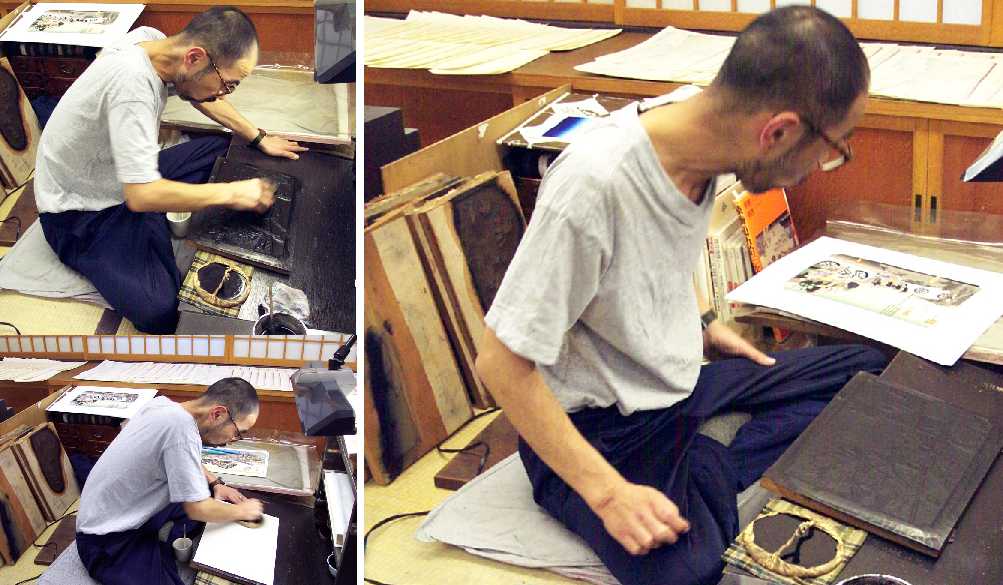

Prior to the actual printing of colors, each blank sheet of Japanese "washi" paper (handmade, typically of mulberry bark) must first be quickly coated by brush with a thin layer of "sizing" which is necessary to prevent the unwanted "side-bleeding" of colored pigments. Once dried, the printing can then begin.

The actual printing, which involves the skillful application and manipulation of colors, is then also a multi-step process. First printed are the black outlines, using the print's "keyblock" as a discussed previously. Black pigment is mixed together with a bit of rice paste ("nori") which is then brushed onto the keyblock's face. One corner and one edge of each blank sheet of paper is then very carefully placed into and against the "kento cuts" as it is laid down onto the (face up) inked woodblock. The actual ink transfer then takes place at the hands of the printer as he quickly, carefully, and with much muscle briskly rubs the backside of the paper with his flat, round, bamboo leaf-covered, handheld tool known as a "baren." This process-in amazingly rapid succession-is repeated with precision until a stack of 50 to 100 sheets are completed.

After being set aside to dry, this process is then repeated again and again, using the differently carved (and differently colored) woodblocks to over-print each individual color. Again, each time, the paper must be carefully set into and aligned with the block's "kento cuts"-one miss-slip and the print is destroyed. And as alluded to earlier, oftentimes "wider areas" of color are additionally carefully manipulated on the surface of the inked woodblock (by brushing and/or wiping away) to produce the wonderful gradations of color (known as "bokashi") we see left on the printed page. Like carving, these printing skills are not learned overnight. (It is reported that one of Doi Publisher's printers, Seki, "trained under (his "sensei") Yokoi from 1955 (when he was 14 years old) until 1965-Seki's own (printers) seal never appeared until 1965.") Quite clearly, these skills can take years to develop.

Finally then, often months after the process has begun, the individual print is complete. These prints are always a wonder to behold-especially when one understands the many steps taken to produce each hand-carved, hand-printed copy. Just below follows a series of photographs illustrating the process you've just read about.

Modern Day Japanese Woodblock Artisans Hard at Work (only the electric lights are new)

Carver-Working on a Print's "Keyblock"

Rapidly Applying "Sizing" to Blank Sheets of "Washi" Paper

Printer-Inking, Rubbing (with "baren"), Finished Sheet

The Finished Print-Hiroshige's "Giant Lantern at Asakusa" (originally done 1856)

OK-a few closing remarks. It was interesting to note that during our 45 minute observation and visit, very little was spoken between these busy and disciplined workers-no "chit-chat," no music playing. My wife Hisako spoke mostly with the young carver seen in the second set of photos. She asked him how he had chosen to learn this arduous and dying art of producing woodblocks. He was seemingly at a loss to explain why. I asked his about his workday. He said he generally "worked 5 or 6 days a week, 8 to 9 hours per day." When asked how long it takes to carve a complete set of woodblocks, he replied "some set took MORE THAN A YEAR." Hisako then inquired, with humor, if he had ever had any serious accidents or made mistakes with a nearly-completed carved woodblock. His answer, "Sadly, yes."

The once very widespread, popular production and corresponding eager consumption of woodblocks by native Japanese during the late-Edo (early 1800's) and Meiji (1868-1912) periods nearly disappeared at the turn of the last century as new mechanical printing methods became introduced into Japan. Somehow, beyond the slimmest margin of practical hope, the production of "shin-hanga" prints was then begun by Shozaburo Watanabe's Print Shop around 1906, when he sought out the few artisans he could elicit, keeping the artform barely alive. A second re-flourishing of print production then occurred during the 1920's through the 1950's, with the 1930 and 1936 "Special Exhibitions of Modern Woodblock Prints" held in Toledo, Ohio helping to spark further interest and demand for prints. However, with the deaths of artists Hiroshi Yoshida in 1950 and Hasui Kawase in 1957, much of the power behind the "new print movement" was lost. Sadly now, few carvers and printers (and even fewer artists) remain.

Today I fear, we may indeed once again be close to the end of Japanese woodblock print production. Just as few young people wish to remain in the countryside to perform the arduous tasks of farming, so too it is also sadly true of the tiny numbers of those willing to learn and carry on many of Japan's handicrafts. Few it seems have the interest, patience, or desire.

(Please note, it has taken me numerous previous trips to Japan before I've actually been able to successfully locate and then observe such work being done-so I trust that reader will forgive my reluctance to reveal my precise sources or contacts.)

The text and images of this article are the sole property of its author, Thomas A. Crossland, Copyright 2000; All Rights Reserved.