Historical Background -- The Evolution of "Kuchi-e"

Historical Background -- The Evolution of "Kuchi-e"

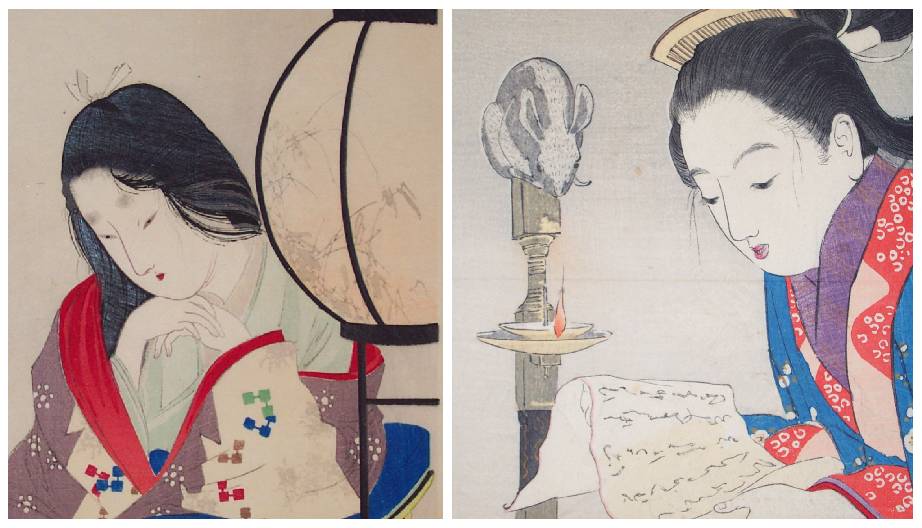

To understand the appearance and evolution of "kuchi-e," one must first have some understanding of the social and political turmoil that occurred in Japan during the last half of the 19th century. Preceding the forceful opening of Japan's borders by Commodore Matthew Perry when he sailed into Edo Bay in 1853 abruptly ended Japan's two centuries of seclusion, Japan had existed largely isolated on its own as a "isolated society." During this earlier period, which lasted nearly 200 years, the Japanese society existed largely away from the influence of other nations and, as a result was largely unaware of the scientific and economic progress that occurred during this time.

To be sure, the Japanese did have some limited contact with the European world during this earlier Edo period (1604-1868), however this contact was strictly limited to the Netherlands, a country which was allowed to maintain only a small trading post on an island in Nagasaki, far from the capital of Edo. Through this contact with the Dutch, the Japanese did learn some about astronomy, a limited knowledge of western medicine, and certain physical sciences, however they badly lagged during this period with respect to many scientific and technical advances.

Perry's 1853 arrival in the capital of Edo with steam ships and powerful cannons changed all that, and the rest is history. The subsequent opening of Japan's borders to international trade in 1859 and the following Meiji Restoration and reorganization of government in 1868 lead to a very rapid and forceful change. Within a single generation, Japan began to adopt and imitate many aspects of western culture, including western modes of fashionable dress and dance, western social customs, western architecture, transportation, international trade, etc.

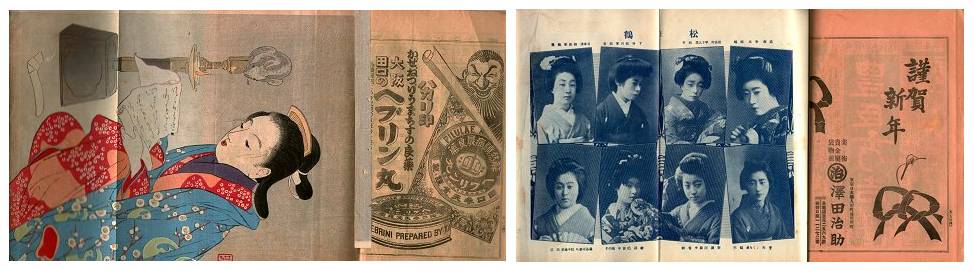

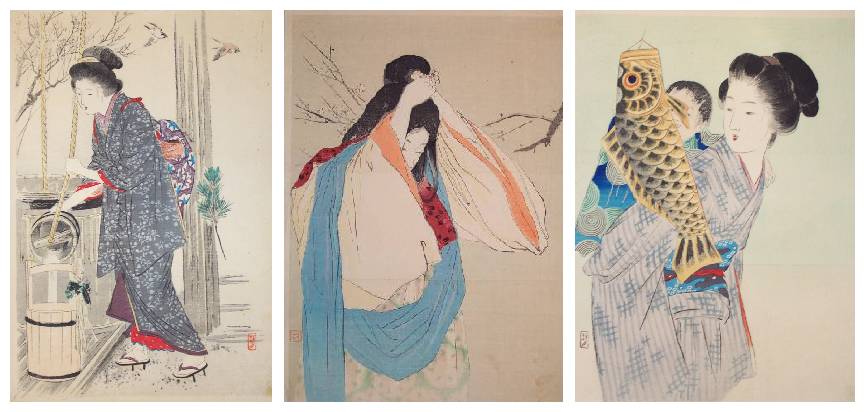

Toshikata MIZUNO's "Bijin Hanging Flags" (1904)

In many ways, the newly "enlightened" and younger Japanese turned their backs on centuries of traditions--likely much to the dismay and hurt of older generations. During this period, the Japanese government played "catch-up" with the west, desiring to become social and political equals with its newly acquired trading partners in the west. With its borders having been breached by foreign powers, Japan's leaders also desired to become militarily powerful, likely mindful of their recent weaknesses. It was therefore a period of much turmoil and very powerful social change.

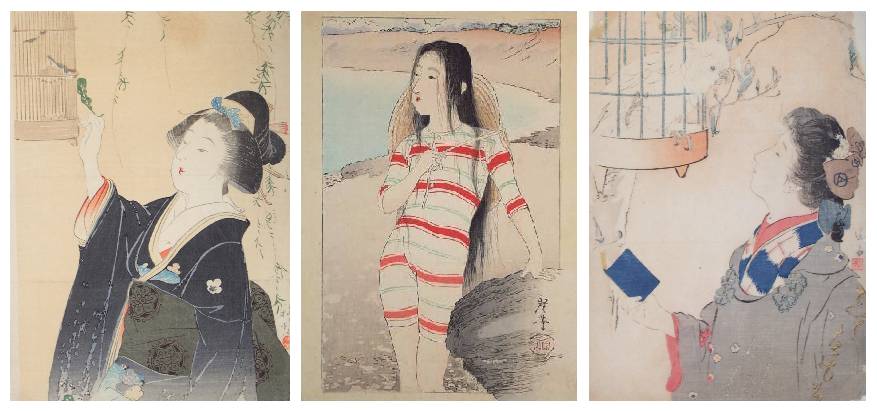

By the 1890's, multi-colored Japanese "ukiyo-e" prints were already beginning to be viewed as "old-fashioned" and "out of date," as the popularity of Japanese woodblocks had already started to become a dying tradition. Some resurgence of Japanese interest then occurred with the release of "war print" woodblock illustrations that were popular during Japan's 1894-95 war with China, however at the same time, western printing presses and lithography were being introduced into Japan, bring severe economic pressure to those publishers that had previously relied on the expensive and labor-intensive production of hand-printed woodblocks.

With many Japanese artisans (and publishers) likely hurting for employment, "kuchi-e" then largely evolved, in this writer's opinion, simply out of economic necessity. The Japanese have always been shrewd and adaptive as businessmen, and so therein likely lay the seeds of "kuchi-e" production. What better way to continue making a living (and a business) of producing woodblocks than to sell them in conjunction with the popular novels and literary magazines of their time? Even today, the Japanese are well-known for their seemingly insatiable appetite for the written word accompanied visually with drawings--one need only to witness the widespread reading of "manga" (comics) by adults on subway trains to confirm that. Likely much of this appeal is due to the "visual nature" of the written Japanese "kanji" and "hirigana" alphabets, and it seems clearly evident that the same love of reading existed a full century ago. Hence, late-Meiji Japan saw the birth of "kuchi-e" as inserts into the popular novels and magazines of their time.

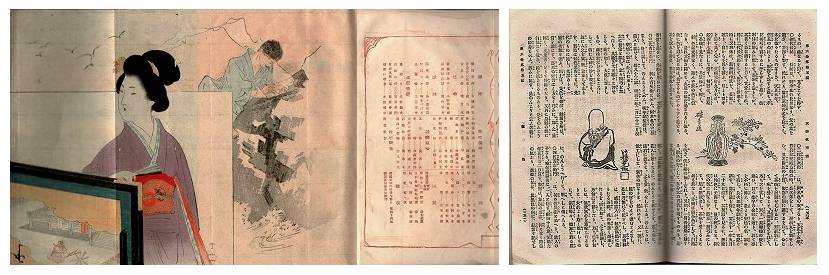

"Bungei Kurabu" Magazine

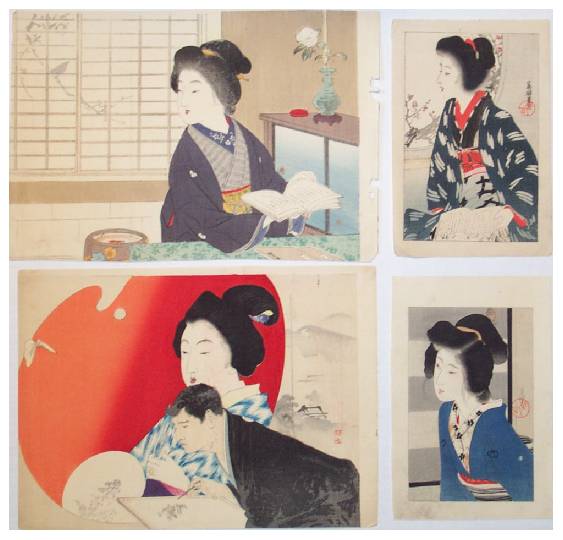

The first widely seen "kuchi-e" woodblocks were produced as inserts into the popular literary magazine "Bungei Kurabu" during the period 1895 to 1914, although some earlier examples are know to have appeared as early as about 1890. During this nearly 20-year period, this widely sold literary magazine produced literally thousands of these "kuchi-e" woodblock illustrations in the form of over 230 individual designs. A couple of examples are shown illustrated below, showing how their "kuchi-e" woodblocks are folded and attached to fit within these tall/narrow novels.

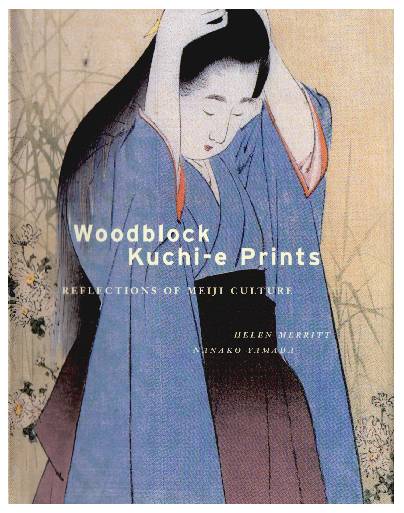

Introduction--What are "Kuchi-e?"

Introduction--What are "Kuchi-e?"